ROCK OF SAGES SERIES: "Baker Street" Gerry Rafferty (#4)

The Soundtrack of a City Soul, and the Sermon We Never Heard

Winding your way down on Baker Street

Light in your head and dead on your feet…

Before a single lyric is sung, a saxophone explodes across the silence—a cry from the marrow, raw and melodic, not asking permission but commanding attention. It doesn’t introduce the song—it is the song, instantly familiar, universally haunting. For millions, it opened a portal into something they couldn’t quite name. For me, it was the first time I remember a song stopping me. Not just because it was catchy. But because it knew something. Something about me. Something about us.

Let’s wind back.

It’s 1978, Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Cambridge Drive. Our basement, worn and war-marked by boys’ adventures. Our kingdom had a soundtrack. WAPL streamed from the corner, and that saxophone riff? It was a kind of neighborhood anthem—ricocheting off the concrete walls of garages and alleyways, mingling with the scent of grass clippings and charcoal.

We didn’t know who Gerry Rafferty was. We didn’t know he was wrestling demons. We didn’t know this song was the sound of a man trying to come home and not quite making it. All we knew was that it pulsed through our pre-teen souls like a riddle we were born to solve.

Decades later, I would come to learn more about the man behind the music. Rafferty wasn’t just some smooth-voiced crooner. He was a haunted poet with a Catholic conscience, a child of poverty and pain, who rose to fame only to find it a gilded cage. After his time in the band Stealers Wheel—yes, “Stuck in the Middle with You”—he tried to escape the music industry’s clutches. “Baker Street” was written in that liminal space, crashing on a friend’s couch in London, trying to get out of a record deal, trying to get out of himself.

The titular street, of course, is most famously home to Sherlock Holmes—fiction’s most famous detective. It’s fitting. Because “Baker Street” is not just a place. It’s a question. A mystery. The kind that requires soul-detective work. Not of crime, but of character. Of truth. Of what it means to be known.

He sings:

You used to think it was so easy

You used to say it was so easy

But you're tryin’, you're tryin’ now.

This isn’t just poetic melancholy. It’s the echo of every heart that ever tried to trade innocence for applause. It’s what happens when a man climbs the ladder he was told would make him happy—only to realize it’s leaning against the wrong wall.

This city desert makes you feel so cold

It’s got so many people, but it’s got no soul…

He could’ve been describing any modern metropolis. Or a school hallway. Or a social feed. Loneliness in proximity. Digital lights that mimic warmth but don’t burn. The empty room where applause once was.

And then—then—comes the part that always leveled me, even before I understood why:

But you know he’ll always keep movin’

You know he’s never gonna stop movin’

’Cause he’s rollin’, he’s the rolling stone…

It sounds like freedom, but it’s not. It’s exile.

A False Promised Land

What makes this song so devastating is not just the confession—but that so few people heard it as such. The saxophone was too seductive. The beat too kinetic. We felt something, but we didn’t listen. It’s the paradox of pop music: the most prophetic songs often dance right past us.

And yet, if we had ears to hear—then and now—what would this song have saved us from?

Would we still be pulling out our phones like compulsive gamblers, not looking for something specific but just scratching the existential itch?

Would we still measure worth by visibility?

Would we still sacrifice presence for performance?

Because long before cell phones and curated selves, Rafferty was already there—sitting on Baker Street, dead on his feet, light in his head, wondering why everything he was told would fulfill him only left him more empty.

And we sang along.

The Lesson We Missed

As a boy, I didn’t know much about inner darkness or the seduction of the stage. But I did know the joy of organizing the neighborhood—kickball at the Carter’s, tackle-asky on the side lawn, ding-dong ditch when the sun went down. I knew that a new kid showing up mattered more than how cool he was. That presence was the currency. And yes, maybe I liked being the ringleader, but not because it made me “popular”—because it made people come together.

We don’t talk enough about what it meant to grow up before the isolation. When joy came from messy people showing up, not curated images being posted. When we didn’t yet pull dopamine from our pockets. And if “everything we needed to know we learned in kindergarten,” it was partly because we lived it in the neighborhood first.

“Baker Street” came to us as a song, but it was always more. It was a warning. A lament. A man saying: I tried it. I followed the script. It doesn't work.

He dreams of escape—land, sobriety, silence. But then he says:

You know he’ll always keep movin’...

Because he’s wounded. Because he’s still chasing something he doesn’t believe he can have.

A Sermon for the Scroll-Worn

What makes this song timeless isn’t just its sound. It’s its wound. It names the ache that algorithms exploit. It exposes the mirage that fame fixes you. And it tells the truth we’d rather avoid: that if we don’t come home, we will keep moving until we disappear.

When Rafferty died in 2011, alcoholism had worn his body down. The man who once wrote, "He’s gonna give up the booze and the one-night stands…” never quite escaped them. But his music did. And that matters.

Because this essay you’re reading? It’s not about a song. It’s about what happens when we stop to listen. To realize we’re not so different. That maybe we, too, have spent years on our own Baker Streets—thinking the city had everything, when it had no soul.

The saxophone still soars. And if you close your eyes, you can still feel it pulling—not toward the crowd, but away from it. Not toward lights, but toward love. Toward presence. Toward home.

So maybe the real gift of “Baker Street” is that it stops pretending. It tells the truth before we’re brave enough to live it.

And maybe that’s where redemption begins.

With a saxophone’s cry.

With a man’s quiet confession.

And with you, dear reader, winding your way down your own street… and finally, turning toward home.

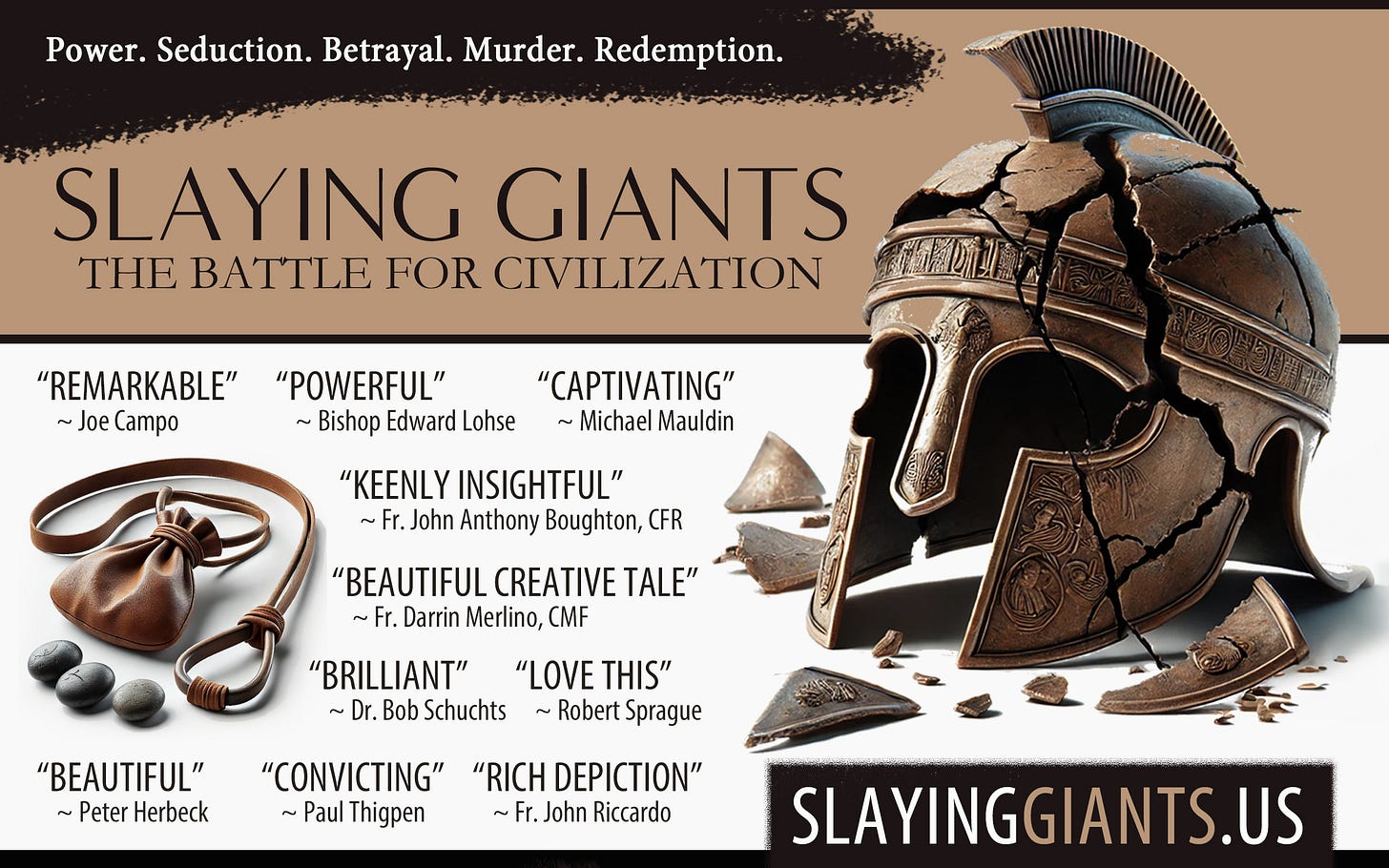

Greg Schlueter is an author, speaker, and movement leader passionate about restoring faith, family, and culture. In addition to directing communication and marketing for the Institute of American Constitutional Thought and Leadership, he leads Image Trinity (ILoveMyFamily.us), a dynamic marriage and family movement, and offers thought-provoking commentary on his blog, GregorianRant.us. He hosts the popular radio program and podcast IGNITE Radio Live alongside his wife, fostering meaningful conversations that inspire transformation. They are blessed with seven children (one in heaven) and a growing number of grandchildren. Recent books: The Magnificent Piglets of Pigletsville, Twelve Roses, and Slaying Giants (SlayingGiants.us).

HELP US SLAY GIANTS at SlayingGiants.us, with a forward by Fr. John Riccardo—a story being called "Captivating," "Beautiful," "Powerful."