I was eight when Bohemian Rhapsody dropped in 1975—too young to grasp its storm, but not immune to its pull. Like so many great songs of that era, it slipped into an emotional time capsule. I wouldn’t truly hear it until high school at Lourdes Academy in my beloved Oshkosh, Wisconsin—when the absurdity of life had grown sharper, the rules more questionable, and our voices more desperate to be heard.

This was the song that made you an opera star.

Didn’t matter if you were off-key or half-buzzed in a friend’s basement. Someone would sing “Is this the real life?” and the room would ignite. You’d belt it out like a liturgy. Not because you understood it, but because it understood you. Somewhere beneath the melodrama and mockery, we all knew: this was about something real.

Mama, I just killed a man…

Not just a line. A confession. A cry. A soul cracking open.

The Bohemian Ache

Bohemian is more than a word. It’s a posture. A spirit. A rebellion.

It meant rejecting moral constraints, religious structure, bourgeois expectations. It was the Woodstock crowd in flowing shirts and bare feet, the artists and poets who chose wine and wonder over rules and reverence. It was liberation—but often, a flight from wounds no one knew how to name.

Freddie Mercury lived Bohemianism like a sacrament—flamboyant, sensual, unpredictable. But if you listen closely to Bohemian Rhapsody, you’ll hear not freedom, but fallout. Not self-fulfillment, but spiritual vertigo. The song sounds like someone who has broken the law of gravity and is now learning how far down the fall goes.

It’s the shape of via negativa—the ancient spiritual tradition that comes to truth not by assertion, but by absence. It’s how we sometimes come to know God best: not through clarity, but through longing. Not through perfection, but through pain. This song punctuates life without God—and by doing so, cries out for Him.

Gospel in Glam

Bohemian Rhapsody wasn’t safe. It wasn’t three chords and a catchy refrain. It was a slow, theatrical eruption—madness and majesty, confession and opera. It gave voice to what most of us couldn’t say aloud:

I’ve failed. I’m afraid. I want to go home, but I don’t know how.

I see a little silhouetto of a man…

That famous middle section—bombastic, bizarre, a courtroom in falsetto. Beelzebub. Thunderbolts. Galileo. It sounded absurd. But listen with spiritual ears and you’ll hear a soul on trial. Shame. Guilt. Desperation.

Spare him his life from this monstrosity…

It’s easy to laugh—until you realize it’s a mirror. Until you remember staring at the ceiling, wondering if grace could really reach someone like you.

Mercury never explained the song’s meaning. But the shape is familiar: sin, remorse, judgment, and a desperate plea for mercy. A gospel veiled in glam rock. A Stations of the Cross in six minutes and some change.

So you think you can stone me and spit in my eye?

The rage. The recoil. The resignation.

And finally—Nothing really matters to me.

The most tragic line in the song. And the most false. Because everything matters. The ache, the longing, the unspeakable regret. That line is not a conclusion—it’s a cover. A mask over the oldest human hope: Please let this not be the end of me.

Scaramouche and the Sacred Clown

Scaramouche, will you do the Fandango?

The line sounds like nonsense—a fever dream from a thunderstorm of theater camp. But the symbols are ancient. Scaramouche was a character in Italian commedia dell’arte: a cowardly clown who masked his fear in swagger. The Fandango? A fierce Spanish dance—defiant, passionate, unhinged.

Put together, they are Mercury’s spiritual stand-ins: a soul trying to dance away its doom.

Because sometimes we joke to cover the ache. We dramatize what we dare not say plainly. We swirl our capes, stomp our feet, hide behind stage lights, hoping no one sees the tremble in our hands. And yet—it’s in the absurd that truth sometimes slips through.

Their nonsense is necessity. Their absurdity, sacred. Because even clowns can carry the gospel.

Mercury Rising

And here’s the thing: Mercury knew faith. He was raised Zoroastrian. Schooled Anglican. Liturgies shaped him. He sang Jesus and Somebody to Love. Spirituality haunted his music, even if he danced beyond its bounds.

He lived outside the lines. But he died facing the truth. Ravaged by illness. Isolated. Mortal. And perhaps—just perhaps—seeing more clearly the God he had always been reaching toward behind the velvet curtain.

The High Church of the Battered Tape Deck

Bohemian Rhapsody took three weeks to record. 180 overdubs. No synthesizers. Just tape, sweat, and genius. When Queen handed it to EMI, executives balked: “Too long. Too weird.” Radio stations shrugged. Until one rogue DJ spun it 14 times in a single weekend—and a generation fell to its knees in a strange kind of reverence.

It topped charts twice. Once in 1975. Again in 1991 after Mercury’s death. It stole the show at Live Aid. But none of that explains why we sang it.

Because it wasn’t about radio. It was about release.

I remember one night in high school—dim lights, red Solo cups, someone pressing “play.” And us—football players, honor students, misfits—becoming opera stars. Screaming. Laughing. Crying. We weren’t mocking it. We were making sense of it. Together.

Some were carrying secrets. Some, suicidal thoughts. Some, wounds from fathers who had vanished or voices that had silenced them. Bohemian Rhapsody gave us permission to feel. To fall apart. To rage and wonder and plead.

It wasn’t theology. But it was grace.

The Law We Broke

Years later, I had a conversation with a former classmate—older than me, beautiful, brilliant, raised Catholic like I was. She’d walked the Bohemian path through high school and beyond. Sex. Drinking. Abortion. Divorce. And now—after all the rubble—Christ.

She said: “All those rules we learned… they just felt so oppressive.”

I had to ask: “But which of those rules did we break that didn’t, in the end, break us?”

It’s the oldest story in the world. Break the law, and you break yourself. Or as Cecil B. DeMille said: We don’t break the Ten Commandments. We break ourselves against them.

Moral law is not tyranny. It’s gravity. And trying to live outside of it is like rejecting the banks of a river and expecting the current not to drown us.

Back to the Crossroads

Now, I hear the song differently.

Not as an escape from religion—but a cry toward it. Not the Church as institution, but the Church as hospital. A place where sins are not hidden, but healed. Where absurdity is not mocked, but redeemed.

Where every soul—even the ones dancing in drag or singing in riddles—finds out that grace is bigger than their shame.

And I think of my classmates. Dave. Augie. Others who are now gone. Not erased. Awaiting. I think of the ones who carried their storms silently. The ones who sang loud because it was the only prayer they had left.

Bohemian Rhapsody didn’t save me. But it cracked the door.

It showed me what life outside the truth looks like. And in its ache, it pointed me toward the light.

Because via negativa is real. The pain tells the story. The absence reveals the need. The scream gives way to the Savior.

The Raging River, the Solid Banks

Truth is not the opposite of freedom. It is the form that makes freedom possible. Like a river’s rapids—it rages, yes, but within its banks. Boundaries do not bind us—they buoy us. They keep the water moving. They keep us from drowning in ourselves.

The Holy Spirit is not a puddle of vague emotion. He is a roaring current. And those banks—formed by the Commandments, by Christ’s Church—do not constrain the soul. They carry it home.

And maybe that’s what this song, in all its absurdity and ache, is finally saying.

You still matter. You can still come home.

And then, just maybe, we find ourselves singing—absurdly, imperfectly, gloriously—

Any way the wind blows…

And trusting that, yes—even that wind may carry us home.

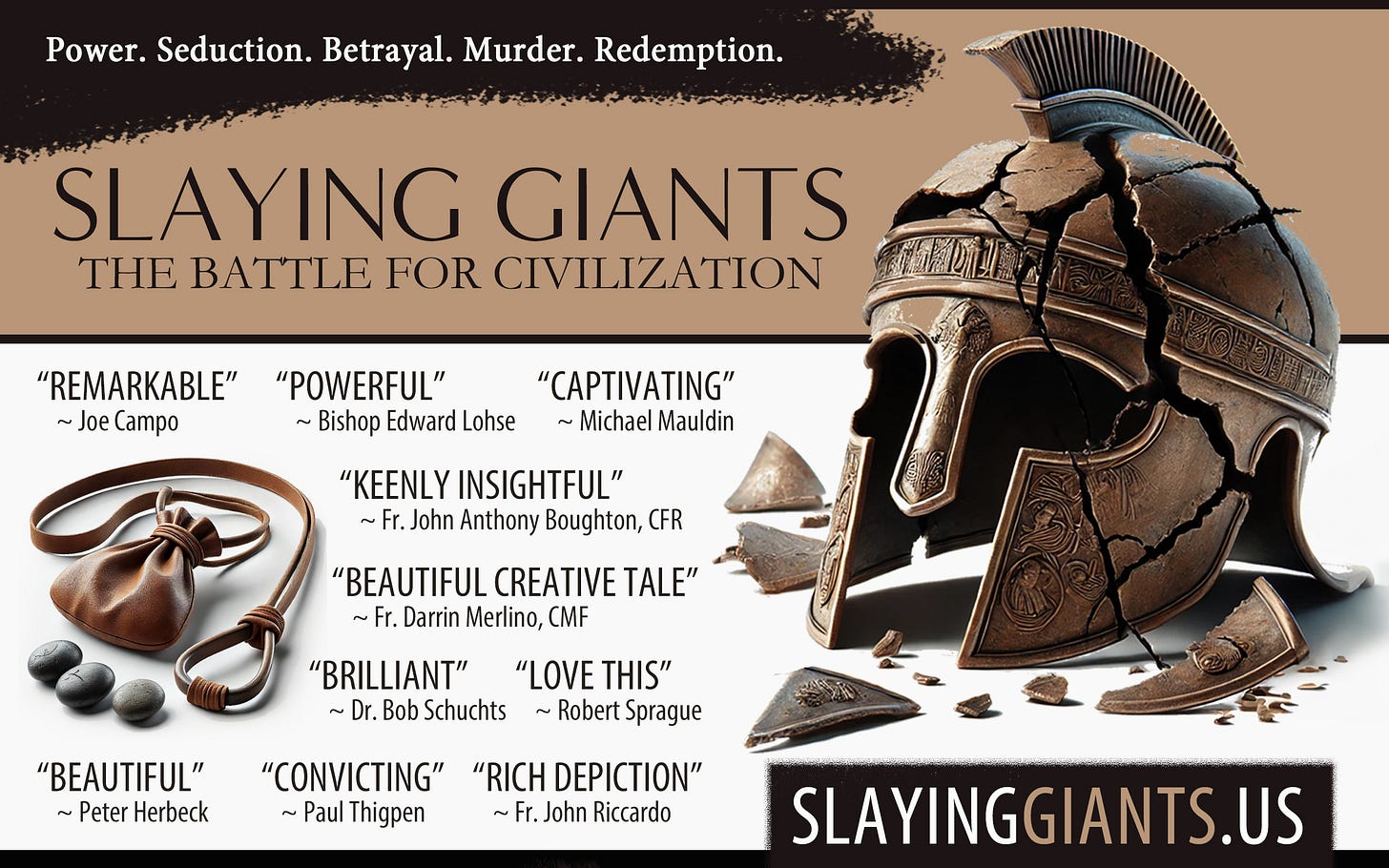

Greg Schlueter is an author, speaker, and movement leader passionate about restoring faith, family, and culture. In addition to directing communication and marketing for the Institute of American Constitutional Thought and Leadership, he leads Image Trinity (ILoveMyFamily.us), a dynamic marriage and family movement, and offers thought-provoking commentary on his blog, GregorianRant.us. He hosts the popular radio program and podcast IGNITE Radio Live alongside his wife, fostering meaningful conversations that inspire transformation. They are blessed with seven children (one in heaven) and a growing number of grandchildren. Recent books: The Magnificent Piglets of Pigletsville, Twelve Roses, Ride Of A Lifetime, and Slaying Giants (SlayingGiants.us).

HELP US SLAY GIANTS at SlayingGiants.us, with a forward by Fr. John Riccardo—a story being called "Captivating," "Beautiful," "Powerful."