The Age of Fragility: Reclaiming Resilience in a Culture of Victimhood

It’s time to form a generation that doesn’t fear the fire, but is forged by it.

Not long ago, a bright and thoughtful young woman opened up during a retreat small group. She shared that she had recently come to view her upbringing as “traumatic.” Gently, the group leader asked her to elaborate. The young woman hesitated, then offered: “Well… my dad was strict. He didn’t really validate my emotions. He focused on my behavior, not my heart. He expected a lot—too much, sometimes.” Almost instantly, others in the circle nodded in recognition, adding their own stories of “toxic expectations,” “setting boundaries,” and even “cutting my parents off.” The leader, who knew many of their families personally, was quietly stunned.

These were homes marked not by neglect, but by deep, sacrificial love—homes where parents, many of them devout Christians, strove not only to guide their children’s behavior but to nurture their hearts. And yet, these young women spoke with the certainty of a verdict rendered. In their world—and increasingly in ours—such ordinary tensions and imperfect relationships were enough to merit the label: trauma.

We live in an age where the words valid and trauma have been stretched, blurred, and brandished like badges of honor. What was once reserved to describe profound violations—war, abuse, life-altering catastrophe—has become a catch-all for ordinary difficulty, disappointment, or discomfort. This redefinition may masquerade as empathy, but in truth, it is a quiet betrayal. It undermines the very human strength it claims to defend. It does not help people heal. It leaves them hollow, defined by wounds that never were.

When Everything Is Trauma, Nothing Is

In decades of Catholic leadership, I’ve seen this shift firsthand. One respected Catholic counselor lamented, “We’ve done a terrible disservice by convincing children that normal emotional struggle means they were harmed—especially by their fathers.” Certainly, fathers can and should be called to nobler standards. But to conflate firm expectations or emotional distance with psychological trauma is to rob children of the opportunity to develop resilience.

Developmental psychology backs this concern. Laurence Steinberg’s research underscores that adolescents thrive with firm, affectionate guidance. Diana Baumrind’s classic framework extols “authoritative parenting”—the balance of warmth and structure—as the most effective path toward maturity. But when ordinary household rules—bedtimes, discipline, curfews—are painted as oppression, we risk raising adults who view responsibility itself as a form of harm.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines trauma as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. And yet today, trauma is invoked for poor grades, sibling rivalry, or being told “no.” This isn’t compassion—it’s confusion. And it comes at a cost.

The Fallout of Mislabeling

Call a scolding “emotional abuse,” and the real victims of such abuse are drowned in the noise. Label a bad grade “psychological harm,” and the sacred work of perseverance is lost. What once made us stronger now makes us stop. What once invited growth now demands apology. What once formed character now forms grievance.

But when we substitute subjective discomfort for clinical trauma, we don’t promote healing—we cultivate helplessness. And when that helplessness becomes institutionalized, it metastasizes into a cultural ethos of grievance and entitlement. Increasingly, even violent crimes and riots are excused as expressions of “hurt,” reframed not as injustices but as misunderstood cries for help. Politicians and media voices legitimize the chaos, cloaking destruction in the language of compassion. In one recent case, after a young man murdered an unarmed teenager, public sympathy and donations flooded in—not for the victim’s family, but for the perpetrator's.

When justice is eclipsed by emotional narrative, when criminal acts are rewarded and innocence is forgotten, we do more than lose our moral bearings—we endorse the very conditions that unravel personal responsibility and the rule of law.

False Gods and Emotional Theology

But beyond clinical categories and social trends lies a deeper question: what kind of God do we believe in?

This confusion isn’t limited to our psychology—it seeps into our theology. Many today embrace an image of God the Father that mirrors contemporary therapeutic ideals: a divine presence who never raises His voice, who always validates emotions, who simply wants us to “be happy,” and who accepts us unconditionally, without expectation or correction. While this portrait may feel comforting, it does not reflect the God of Revelation.

Scripture presents a far more complete—indeed, more loving—vision of the Father. He is the One who spoke from Sinai in thunder and fire (Exodus 19), who cast Adam and Eve from the Garden (Genesis 3:23–24), who warned repeatedly of judgment and hell (Matthew 10:28), and who sent His own Son to suffer and die for the redemption of the very ones who rejected Him (Romans 5:8). Jesus, the “image of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15), overturned tables in the temple (John 2:15), rebuked the Pharisees as “whitewashed tombs” (Matthew 23:27), and named their blindness for what it was—moroi in Greek, the root of our word “morons” (Matthew 23:17). These are not the actions of a passive, permissive deity, but of a Father whose love is fierce, purifying, and purposeful.

To affirm that “God is love” (1 John 4:8) is not to embrace a sentimental abstraction, but to encounter a love that calls, commands, and conforms us to holiness. The Father’s love is seen not in sparing His Son from suffering, but in allowing Him to walk the road of the Cross—and inviting us to follow (Luke 9:23). In this light, many common critiques of earthly fathers—“He was too strict,” “He expected too much,” “He didn’t explain everything”—reflect not failures of love, but echoes of its true shape. Love that protects must also require; love that dignifies must also demand. No parent, divine or human, acts in love by replacing holy challenge with emotional ease. To confuse affirmation with salvation is to substitute comfort for conversion.

In an age eager to enthrone a therapeutic “Feeling-God,” we are called to recover the God of Scripture—the Father of Jesus Christ—whose love sets boundaries, refines hearts, and ultimately leads us to glory.

From Victimhood to Victory

The real enemy here is not hardship, but a worldview that makes hardship unendurable. Victimhood has become an identity—a badge, a currency, even a career. In this economy, healing is delayed indefinitely because victimhood pays emotional dividends. But the cost is steep: anxiety, despair, dependency, fragility, isolation.

Martin Seligman’s studies on learned helplessness show that people who believe they have no agency become paralyzed—even when escape is possible. Like fleas trained to leap no higher than a jar’s lid, many today live within limits that no longer exist—confined not by pain, but by perception.

Yet history is filled with those who suffered truly—and rose. Immaculée Ilibagiza survived genocide. Viktor Frankl found hope in Auschwitz. Their stories reveal that we are not defined by what happens to us, but by how we respond. As Frankl famously wrote: “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing… to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

The Father’s Love and the Fire That Heals

Our faith is not blind to suffering. It enters it. Transfigures it. Through the Cross, Christ reveals the paradoxical truth: we are not saved from suffering but through it. Pain is not pointless; it can be redemptive. We are not meant to be preserved in emotional amber. We are meant to become saints.

The Catholic vision of the person is exalted: made in God’s image, called to glory, and equipped—by grace—for greatness. We believe in healing, yes, but not the healing of avoidance. The healing of transformation.

When Jesus announced His mission in Luke 4—to proclaim freedom for prisoners and sight for the blind—He wasn’t inviting us into perpetual fragility. He was calling us into freedom. Not the freedom of evading pain, but the freedom of rising from it.

A Call to Courage

We live in a world drunk on self-expression and allergic to self-mastery. But maturity is not measured by the intensity of our feelings, but by the integrity of our response. True mental health professionals know this. So do wise pastors. The future depends on rediscovering the beauty of resilience.

In The Coddling of the American Mind, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt warn that inflating trauma leads not to sensitivity, but to paralysis. Jean Twenge’s research concurs: overprotection breeds anxiety. In shielding our children from pain, we’ve left them unarmored for life.

But this is not the end of the story.

Resilience is real. It can be taught. It can be lived. Research by Southwick and Charney (2012) reveals that people who lean into responsibility, faith, and perspective emerge stronger from adversity—not in spite of it, but because of it.

It’s time to reclaim the word trauma for what it truly means—so we can walk alongside the truly wounded, and help them learn to walk again. It’s time to form a generation that doesn’t fear the fire, but is forged by it.

To rise—not as victims, but as victors.

Not as fragile, but as free.

Not as defined by our hurt, but by the healing power of Christ.

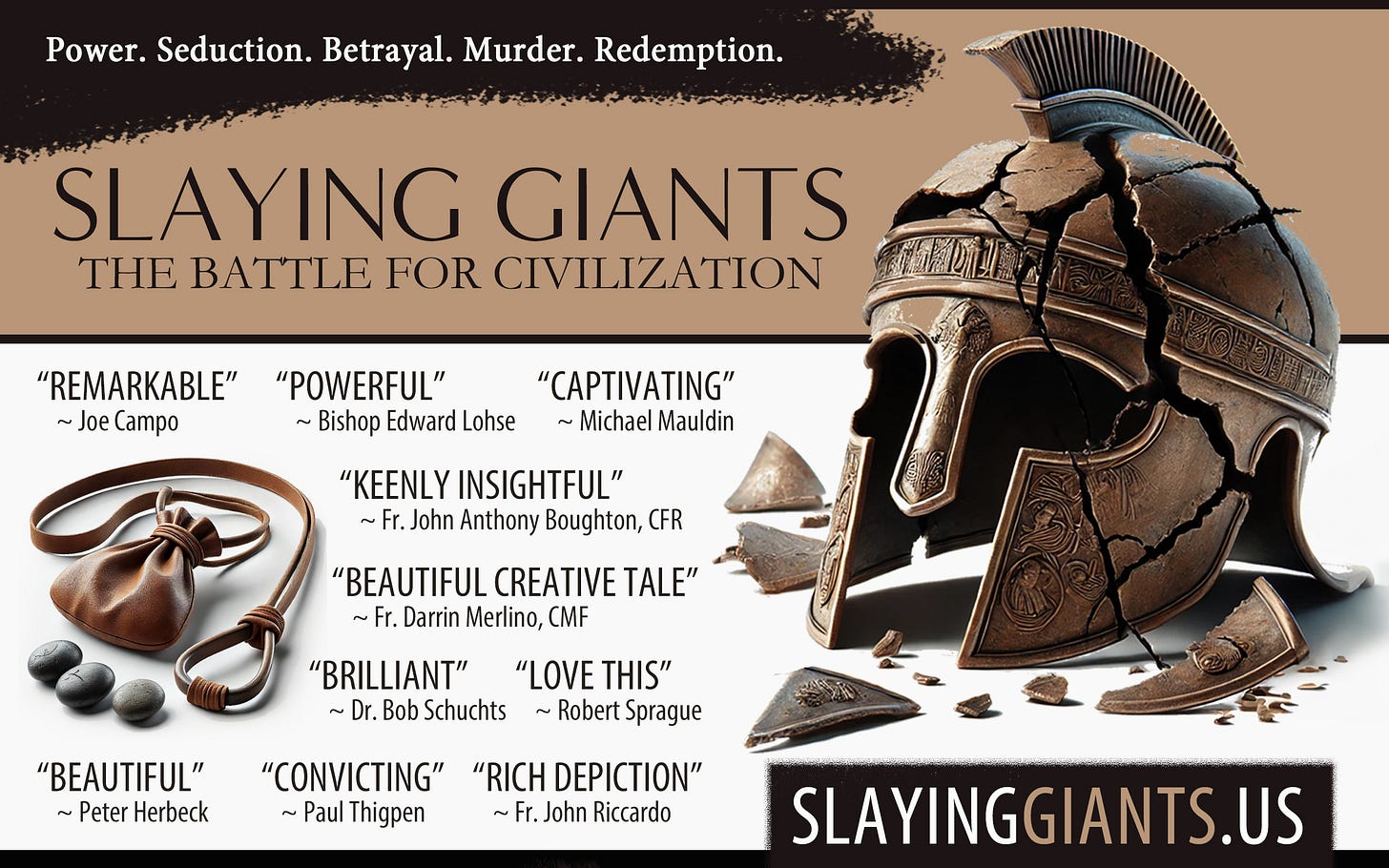

Greg Schlueter is an author, speaker, and movement leader passionate about restoring faith, family, and culture. In addition to directing communication and marketing for the Institute of American Constitutional Thought and Leadership, he leads Image Trinity, a dynamic marriage and family movement, and hosts IGNITE Radio Live. His blog is GregorianRant.us. His recent books include The Magnificent Piglets of Pigletsville, Twelve Roses, and Slaying Giants (SlayingGiants.us).

HELP US SLAY GIANTS at SlayingGiants.us, with a forward by Fr. John Riccardo—a story being called "Captivating," "Beautiful," "Powerful."